The dredger in MacArthur is not just slicing through tilled land, but destroying an entire ecosystem's ability to hold water and putting the community’s livelihood at risk.

Only a measly 3.23% of the ₱1 trillion worth of climate-related projects under the proposed 2026 budget is allocated for food security, which allows industrial mining to sideline agriculture even in critical watershed areas.

While the mining firm was officially under a "care and maintenance" status, it hauled nearly ₱450 million worth of iron ore from the town’s soil. This triggered a "drawdown" effect that has already drained Bito Lake by up to three meters.

This report reveals a massive 80% jump in magnetite production in 2024, providing the data that connect a period of hyper-extraction to the rapid drying of Leyte’s soil.

---------

LEYTE, Philippines - Jose Cabias Jr. stands near what used to be a lush coconut grove, watching a massive ship with a steel arm clawing above the earth. For the lifelong resident of MacArthur town in Leyte, the machine is a monster eating its way toward the town’s lifeline.

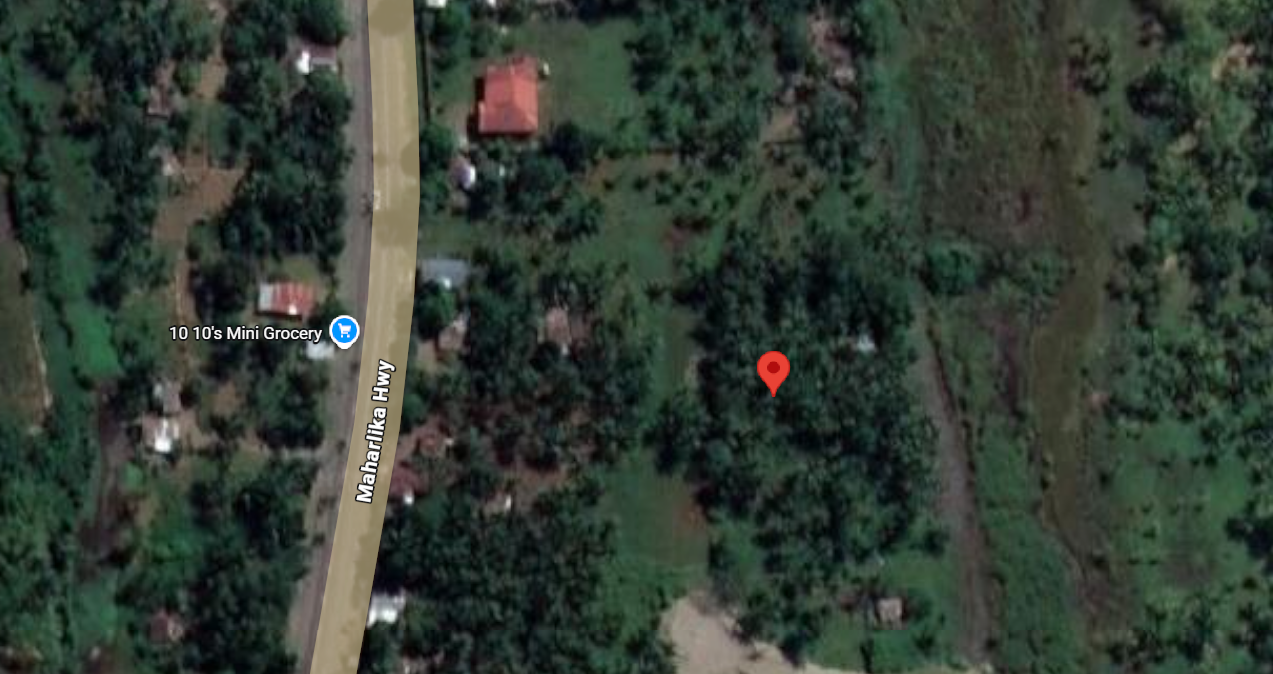

The machine, a cutter suction dredger known as the MV Li Long, is currently parked just five meters from the Maharlika Highway in Barangay Maya. It has moved from the coastline deep into the town’s interior, slicing through coconut plantations.

“It came from the sea, until it reached close to the highway,” he told Fyt in Filipino.

But while the dredger looms over the national road, its most devastating impact remains invisible to the naked eye, hidden deep within the soil.

For Cabias, the sight is a haunting recurrence.

The fight against black sand mining in MacArthur began as early as 2010. Back then, operations under Nicua Mining Corporation were granted 25-year permits through a Mineral Production Sharing Agreement (MPSA) that allowed for the extraction of magnetite and sand.

The town saw the consequences of this early on.

In May 2012, residents reported that the lake’s water had turned a reddish-brown due to heavy siltation from the mining. A massive fish kill devastated the community that same year when 27,000 kilos of tilapia died due to backflow from mining settling ponds, which led to a years-long suspension of operations, Cabias said.

But by 2020, the industry returned under a new name: MacArthur Iron Projects Corporation (MIPC). The company marketed itself as a “responsible” alternative, but Mines and Geosciences Bureau (MGB) records say it was technically under a “Care and Maintenance” program, a status usually reserved for mines that are inactive but kept in a state to restart.

While the project's feasibility was approved as far back as 2011, MIPC’s actual authority to conduct mining operations was only signed on November 11, 2020. The MGB also noted that the tenement sits directly within the critical watershed area of several major waterways, including the Daguitan, Gibuga, and Ubun rivers, as well as the Balire and Bito rivers.

The reality on the ground tells a different story. Data from the National Irrigation Administration (NIA) show that mining has already destroyed 13.79 hectares and damaged another 43 hectares of irrigated agricultural land.

"They said they would mine temporarily, and immediately return it. But what about it now? Since 2020... it has not been returned, the people have not been able to plant on it," Cabias noted.

Following intense local protests and human barricades, the company temporarily withdrew the dredger on February 19 to “maintain harmony and prevent further escalation.”

MIPC added that it would “re-evaluate its current work plan” in coordination with local government units. Despite this pause, the company remains firm that its operations are “environmentally sound.”

But local residents and advocacy groups remain unconvinced. In a February 9 statement, The Bagong Alyansang Makabayan – Sinirangan Bisayas (BAYAN-SB) said that having a permit is “never enough reason to set aside the welfare of the people.”

The interests of big companies should not prevail over the lives and safety of the community, they added.

In 2011, a Visayas State University study looked into the effects of mining in MacArthur. Its findings were a warning that the town is now living through.

The study found that the soil in this part of Leyte has high “hydraulic conductivity,” where the ground here acts like a giant sponge rather than a solid bowl. Water flows through it with extreme ease.

When a miner digs a pit 10 to 15 meters deep to suck out sand, it creates a “drawdown” effect. This happens when the water level in the surrounding area is lowered because it is being sucked into a deeper hole nearby.

The study’s data estimated that for every single hectare excavated, as much as 44,603 cubic meters or 44.6 million liters of water could be drawn out from the surrounding environment into the mining pit.

Continued excavation would likely disturb the water budget of the nearby Bito Lake and “endanger the year-round water supply,” the report read.

Over a decade and a half later, the lake is drying up.

“The lake has already dropped by two to three meters,” Cabias said. "Before, the tilapia there would reach two or three per kilo... Now, it's 12 pieces. The tilapia are not growing anymore and the lake has become silted due to the mining."

The crisis in MacArthur mirrors a larger national trend where food security is often sidelined for industrial and infrastructure goals.

Nearly P1 trillion is tagged for climate-related projects in the proposed 2026 national budget, but Fyt previously noted that the budget remains heavy on infrastructure. Data shows that only 3.23% of that climate budget is allocated toward food security.

In MacArthur, the MIPC project promises economic growth. In a media statement, the company stated that the project would contribute over P100 million in annual taxes and regulatory fees. They added that they have posted a P56 million rehabilitation bond to ensure the “proper restoration of mined-out areas.”

Local officials have used this legality as a shield.

In an official statement, MacArthur Mayor Rudin Babante said that the company’s operations have a “legal basis.” He added that while the LGU exerted efforts to move the dredger back to ease public worries and fears, the mining remains legitimate under existing MPSAs.

But for the residents who have formed human barricades to stop the MV Li Long, legality does not put food on the table.

The VSU study reported that ponding – the filling of deep mining pits with water – is almost guaranteed because of the soil type. This makes it nearly impossible to ever revert the mined areas back to productive rice fields.

In an open letter addressed to President Ferdinand Marcos Jr, concerned residents wrote that without intervention, they would eventually have “no food to feed our families.” Black sand mining leads to the “destruction of our irrigation systems and rice farms,” they said.

As the MV Li Long is idle, Cabias remains firm on the frontlines. For him, the struggle is about the right to keep the land his ancestors tilled for generations.

“It wasn't the government that made these rice fields, it was our ancestors,” Cabias said. “These minerals of ours are just being taken... Who benefits from this? The corrupt politicians and the giant miners." — fyt.ph